Credit: Martin Whiting, author provided

Invasive species provide a rare research opportunity, as they often colonize new environments very different from their original habitat. One such species is Jackson’s three-horned chameleon (Triocerus j. xantholophos), which was accidentally introduced to the Hawaiian Islands in the 1970s.

Our study was published today in science progressshows that Hawaiian chameleons display brighter social cues than individuals from their native East Africa—and could represent an example of rapid evolution.

Long way from home

In 1972, about 36 Jackson’s chameleons made their way from their native Kenya to the island of Oahu in Hawaii, destined for the pet trade.

The chameleon was slightly worse in wear on its arrival in Hawaii, after a long and exhausting journey that would have begun days before it was loaded onto the plane in Nairobi.

The story goes that Robin Ventura, owner of a pet store on Oahu, opened the box in his garden to give them fresh air and a chance to recover. He supposedly underestimated the speed at which chameleons could move (and recover) – and soon spread to the surrounding area.

This founding group represented an accidental invasion and thus became an unplanned experiment in evolution. What happens when an animal with colorful social displays – from a group with lots of predatory birds and snakes – is introduced to an island virtually free of predators?

A male Jackson’s three-horned chameleon (above) courting a female (below) in Kenya. Credit: Martin Whiting

Evolution at work?

We speculated that Hawaiian chameleons, as a result of being relatively free from predation, would have more elaborate or brighter displays than their Kenyan counterparts. We also expected that they would be more visible when seen by predators in East Africa, such as birds and snakes.

In the animal kingdom, bright or colorful displays can attract the attention of sharp-eyed predators. This reduces the animal’s likelihood of surviving and, accordingly, its ability to reproduce (or the number of genes it passes on to future generations).

When survival is threatened, natural selection acts as a brake and stops further color detailing, or changes bright colors to areas of the body less noticeable to predators.

For example, many species of lizards have bright colors hidden on their undersides or throats. In South Africa, male flat lizards will signal to rival males by raising their underside and exposing the throat, which is swollen.

On the other hand, clear performances may also increase fitness. For example, brighter or more colorful males may gain greater access to females, either by winning competitions with competitors, or simply by appearing more attractive to females.

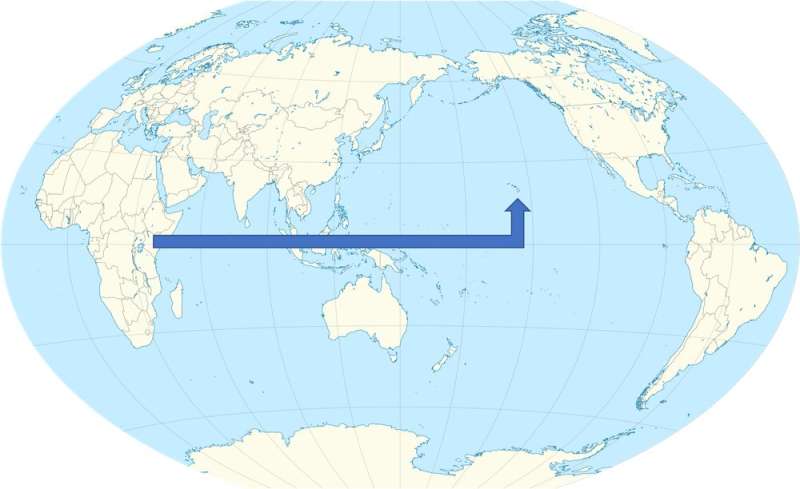

Invasive chameleons reached the Hawaiian Islands – the most isolated island archipelago in the world. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The tug of war between survival and fitness has been well documented in species that are color-consistent or season-dependent. For example, guppies become less hot when dangerous predators share their streams. However, it is less understood in animals with dynamic color change such as chameleons.

Although we have a good understanding of how chameleons change color, we don’t know if they adjust their displays when there are more predators in their environment. It may also be that natural selection prevents them from producing bright or colorful color cues that exceed a certain threshold.

To test our predictions, we traveled to Kenya and Hawaii to study color change in wild chameleons.

Vibrant test themes

Chameleons are great study subjects because they have a very strong motivational response. You can blow them up on a branch away from their usual places and present them with a fake predator or another chameleon, and they will devote all their attention to the trigger while completely ignoring you.

We introduced to each male chameleon a competitor male and female, a typical flying predator and a model snake predator – all in a one-on-one interaction. During presentations we measured their color using an optical spectrometer.

Many species of lizards, such as the flat Augrabies lizard, have brightly colored parts of the body that are less visible to predators such as birds. Credit: Martin Whiting

This tool allows us to specify two color scales: chromatic contrast (the extent of their color mainly) and luminance contrast (how bright they are). We can then estimate the extent to which an occasional chameleon can be detected by the observer – whether it is another chameleon, a bird or a predator.

We also measured the lush vegetation that forms the background to which the chameleon is referring. This way we can estimate the extent to which an occasional chameleon can be detected against a given background.

An interesting example of rapid change

The results were particularly exciting and exceeded our expectations. We found that Hawaiian chameleons had brighter displays than Kenyan chameleons during male competitions and when courting females. They were also more visible on their Hawaiian background than their Kenyan background.

This is consistent with what scientists call “local adaptation.” This is the idea that signals will be fine-tuned to be more detectable in the environment in which they are used.

For the Hawaiian chameleons, one unintended consequence of being brighter was that they were also more detectable by their native predators.

Interestingly, this effect was more pronounced when encountering birds than snakes – possibly because snakes have less color discrimination than birds. Finally, the Hawaiian chameleon also had a greater ability to change color than the Kenyan chameleon—it could do so on a larger scale.

We can’t be completely sure that the brighter signs in Hawaiian chameleons represent a rapid development. It is also possible that this degree of color change is due to plasticity, that is, when the animal changes to a different state due to the prevailing environmental conditions.

However, plasticity itself can evolve—and the color change in chameleons may be a combination of both evolutionary change and plasticity.

Video: Chameleons are masters of nanotechnology

Martin J. Whiting et al, Invasive chameleons released from predation show more vivid colours, science progress (2022). DOI: 10.1126 / sciadv.abn2415

Introduction of the conversation

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

the quote: The tug of war between survival and fitness: How chameleons get brighter without predators (2022, May 12), retrieved on May 12, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-05-war-survival-chameleons -brighter -predatorsaround.html

This document is subject to copyright. Notwithstanding any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.